The story of the Aalto Centre in Seinäjoki

Text: FT Marjo Kamila and Kari Hernesniemi (Oddmob) Illustrations: Kari Hernesniemi (Oddmob)

It is said that the city centre of Seinäjoki was a design and implementation project that was dear to Alvar Aalto’s heart. Seinäjoki is also said to be “the world’s most Aalto-esque city” especially because it was Alvar Aalto’s ideal image of how he thought of a modern urban centre as a whole in tune with nature. All six buildings are grouped around the same marketplace and series of open areas. This unique group of monumental buildings is a protected area.

In church

It is a summery June day in the year 1960. The air feels a little fresher following a severe thunderstorm. Anneli hops over puddles. She stops and looks up at the Southern Ostrobothnia Civil Guard Headquarters. Anneli knows that the building is an early work by Alvar Aalto. She recalls that the building was finished in 1925, a few years after Aalto became an architect. And back then the architect had no idea how famous he would become, Anneli thinks in her head.

For years Anneli has admired the proud, new-classic air of this three-storey building. She also sees features of Ostrobothnian building traditions in the building. Anneli has been inside the building and knows that some of its interiors, furniture and lighting were designed by Aalto himself.

At the corner of the building, Anneli takes a few steps toward the courtyard. Her gaze circles around the two-storey brick building, wooden shed and pergola in the courtyard. She knows that they were also designed by Aalto.

Anneli continues on her way along the uneven gravel road. It is peaceful. She passes two cyclists, a farmer with his horse and cart, and a rumbling truck going the other way. From up ahead comes the whistle of a train leaving the station. Anneli has heard that the junction station formed by the railways of her hometown is called the “mother of Seinäjoki”.

The railway station has caused the community’s residences and centre to shift from the Törnävä area to the area around the station. Now even the old church is too far from its parishioners.

Anneli stops and gazes at the broad, green landscape of fields around the new church that was just consecrated in April. The bell tower of Lakeuden Risti (‘Cross of the Plain’) rises high and strong above the South-Ostrobothnian plain. Anneli thinks that the houses at the edges of the fields look like play-houses compared to the church.

Anneli opens the church’s heavy front door and steps inside. Light falls through the windows in the door, reaching the open door of the church hall. Anneli stops and looks around, awestruck. In front of her, the grand, spacious and bright cathedral opens up. She starts to slowly walk toward the altar.

Anneli finds it almost unfathomable that such a magnificent church can have been built in her home town, Seinäjoki, with its nickname ‘Mud Town.’ Even if the town didn’t get the cathedral chapter. She is glad that the design of the world-renowned architect Alvar Aalto was implemented in the end, even though the design by Aalto’s office did not follow all of the competition rules. Anneli has become acquainted with the works of Alvar Aalto thanks to the newspapers and has begun to admire his reductionist form language.

The modern style of building churches stirred up murmurs in Finland among the regular folk as well as widely among the clergy of our country. And the style of the church being built didn’t appeal to everyone in Seinäjoki, either. Moreover, the poverty of the congregation was a difficult issue during various phases of the church’s construction. It was even thought that perhaps erecting the bell tower should be given up due to lack of funds. The parish council didn’t want to further anger the members of the congregation who were sceptical of the church’s construction, and the church tax was not increased. They wished to fund the construction work through loans, voluntary contributions and donations. Alvar Aalto’s idea of covering the outside of the church in black granite was abandoned before work even began.

Anneli stops beside a pew made of red heart pine, touches its smooth surface, sits down and realises that the pew is unusually nice. Sitting here feels completely different from sitting on the slanting old church pews. She is glad that she has also been able to play a minute part in the building of the church. Anneli is one of many who donated to fund the church pews. Over half of the pews were acquired with donated funds. Even Seinäjoki’s schoolchildren participated in the fund-raising.

In spite of opposition, the church and its tower were completed. Anneli knows a carpenter and has heard how much fondness the carpenters feel for their achievement. Building the church was quite demanding. Construction of the bell tower went on around the clock for three weeks under difficult conditions. The quality and punctuality of the work were important to the men, however, and so the carpenters even competed with one another over how much they could get done during their 12-hour work session.

Anneli continues her walk toward the altar. She stops by a plain cross designed by Aalto. The cross functions as an altarpiece. The architect was of the opinion that there were quite enough overdecorated churches and schooled his critics: ‘That which is accepted quickly and easily is cheap. Time will make Lakeuden Risti into an Ostrobothnian church and into the Ostrobothnians’ church.’

Anneli’s purpose on this visit to the church is to see the baptismal font, since her first-born will soon be baptised there. She finds that the intimate size of the chapel creates an interesting contrast to the festivity of the church hall. A soft bluish light filters through the stained-glass window called ‘The flow of life,’ which was designed by Aalto. Anneli strokes the edge of Aalto’s silver baptismal font and realises that acquiring this also required donations from regular people. She is moved by the fact that the famous architect has truly designed everything for our congregation, from the church textiles to the candle-holders and altar vessels. She heard that he drew many individual items on pieces of paper on the spot while visiting the work site.

Southern Ostrobothnia Civil Guard Headquarters

• An early work by Alvar Aalto, epitomising new classicism, from 1925.

• Aalto designed some of the building’s interiors, furniture, lighting and other details.

• The building has been preserved in its original condition. Currently it houses the Civil Guard and Lotta Svärd Museum. The building is managed by the Provincial Museum of Southern Ostrobothnia.

• The outbuildings hold exhibition and meeting spaces, an info booth and museum store.

• The buildings along with the yard were protected by a building protection law in 2002.

Lakeuden Risti

• The architectural contest for Seinäjoki’s church was organised in 1951, but the church wasn’t built until the years 1957-60.

• The planned name for the church was Lakeuksien Risti (‘Cross of the Plains’) because the church was supposed to become the cathedral of the diocese. The diocese was located in Lapua, however.

• Alvar Aalto has planned the church and baptistery down to the details, such as the lighting, silver altar vessels and church textiles.

• On the east side of the church building is the Church Yard, designed by Alvar Aalto and bordering on Pajuluoma.

• The Church Council made Lakeuden Risti a protected place in 2003.

Blue surfaces and gusts of win

We are in the year 1961. Trees sway around Anneli and Matti-Alvari, singing the wind’s greetings. Matti-Alvari sits happily in his pram and laughs each time that the wind tries to carry away his mother’s brown wool hat.

‘My goodness, what a wind!’ Anneli cries. A sly gust surprises her and snatches the hat off her head. Anneli’s carefully twisted bun falls open and her hair dances in the wind. Matti-Alvari finds this so amusing that he almost falls out of his pram.

Anneli hastily runs after the hat, her hair fluttering in the wind, desperately pulling the pram along behind her. The metal pram rattles over the gravel road. The hat comes to rest against the wall of a work site at a bend in the road. At last, Anneli gets her hat back. She quickly sets the hat back on her head, her cheeks a little flushed from the sprint.

Anneli raises her gaze up from the ground and sees in front of her a building, the progress of which she has followed with great interest. The work site is for the construction of the Seinäjoki City Hall, and the designer of the building, selected through an architectural competition, is the Academician Alvar Aalto.

Industrious workmen are busy laying dark blue ceramic rods, which were made at the Arabia factory, into individual settings on the façade of the building. The rods stand up straight in their settings like tin soldiers. Further along, stretches of installed settings are visible. This would be one of the first times that these blue rods designed by Alvar Aalto are used one such a scope to decorate a façade, Anneli recalls hearing.

Aalto got the inspiration for the tiling on his trip to Baghdad, where he had been invited to design the main post office and art museum. Matti-Alvari also gazes spellbound at the building façade nearing completion, pointing at it with his finger. It’s impossible not to notice the façade, so intense and beautiful is the shade of the dark blue clinker. It might well become the City Hall’s most recognisable and memorable feature.

It’s been said that there will be a theatre and adult education centre in the basement level of the City Hall. Anneli was glad to hear it; things for the edification of the people are important to her. The building would become a familiar place to Anneli and Matti-Alvari anyway — there was also going to be a maternity clinic and dentist’s office there.

Just like Lakeuden Risti, the City Hall had also gotten its own embankment to break up the flat – to some, boring – plain. Anneli and Matti-Alvari continue on their way from the ‘clinker factory’ toward the church, when they notice an extraordinary sight along School Street. A shortish gentleman is making eyeball measurements over an upraised plate toward the Lakeuden Risti tower, hat askew on the back of his head. Four beefy men can barely hold the plate upright, the wind is so strong. It looks like the man is trying to see that the thick wall of the parish centre that will be attached to the church will not block the view of the church tower. From his gestures, it seems that the height is correct. In that moment, with a start, Anneli recognises the gentleman.

City Hall

• Aalto’s office did not do well in the first design contest for a town hall in 1958. In the second round of competition. Aalto won overwhelmingly. The City Hall was completed in 1962, two years after Seinäjoki received city rights.

• The most recognisable feature of the City Hall is the material of its façade. The dark blue ceramic rod tiles contrast with the church and the other buildings on the square.

• The most important place in City Hall is the tower-like city council assembly hall. Due to its good acoustics, music performances are also held there.

Trip to the City Library

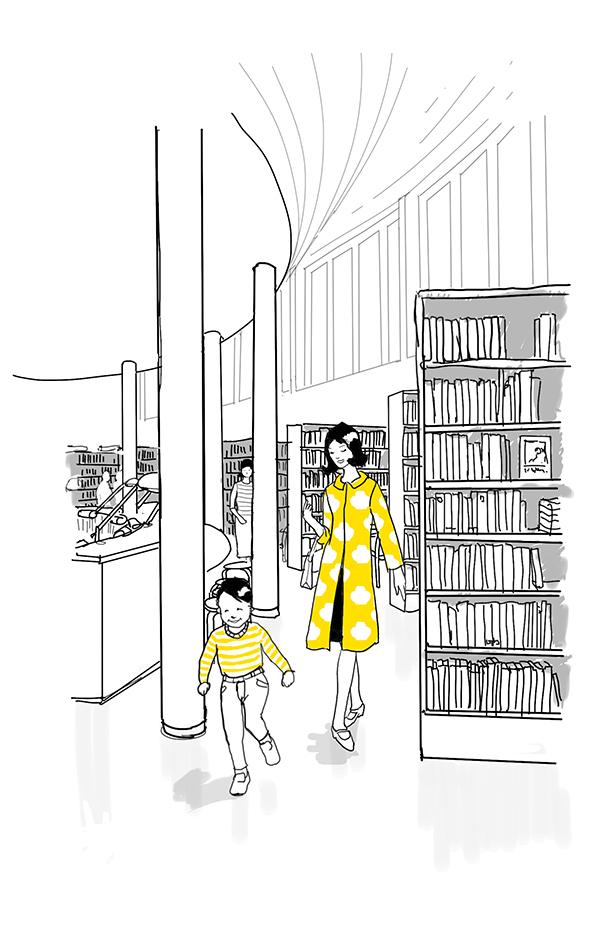

‘Hurry, mum!” Matti-Alvari shouts excitedly to his mother. Anneli follows the speedy boy at a half run, looking around from time to time to make sure she doesn’t embarrass herself with her running. They are going for the first time to visit the Seinäjoki City Library, which was just recently completed, as was written in the papers.

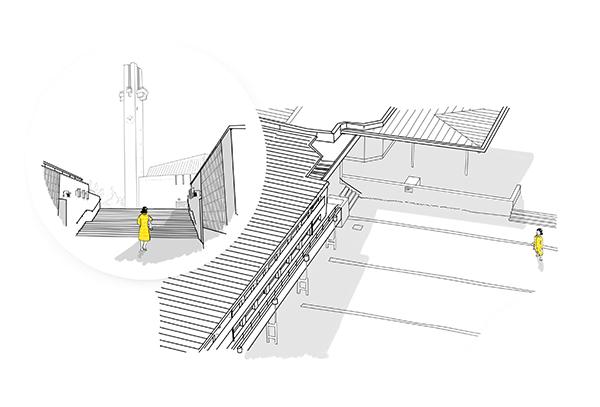

The library is located to the south of the City Hall. The buildings are separated by a walking area reserved for pedestrians, where a Citizens’ Square connecting the buildings is intended to be built — a ‘piazza’, as Alvar Aalto called it in his design, alive with bustling people. The library forms as it were the southern wall of this square, with the City Hall to the north and Lakeuden Risti to the east.

The library’s northern façade is not as festive as that designed by Alvar Aalto. It is quite simple and serves as a contrast to the monumental City Hall. In order to save money, the construction committee demanded that Aalto remove the cloister from the façade, to which the Academician agreed. Otherwise the general tone of the building is the same as the church on the other side of School Street and westward-extending wing of the City Hall.

Anneli and Matti-Alvari open the door to the library. The door handle has a familiar feel. They step inside timidly and are careful to close the door quietly, since one must respect others in a library. Anneli looks around and reaches for Matti-Alvari, but the boy is already off.

‘Mum, there are so many lamps here!’ Matti-Alvari shouts excitedly. Anneli puts her finger to her lips to remind her son how one should behave in a library. Matti-Alvari is a little embarrassed but continues in a whisper: ‘They’re all different, or almost all of them. There are so many in a row. How come we only have one at home?’ In the reading room, Anneli points out a dark blue lamp to Matti-Alvari and asks: ‘What does this remind you of?’ ‘A blueberry!’ Matti-Alvari exclaims – and then remembers how one should behave in a library. Anneli gives a little laugh and states: ‘Right. These lamps were designed just for our library and so they are completely unique.’

In the circulation area there is a recess, where there is a row of, in Matti-Alvari’s opinion, funny-shaped tables in a row – as well as more lamps of different kinds. ‘There’s also a children’s section here’, Anneli exclaims to her son. In the blink of an eye, Matti-Alvari comes out of the recess and runs toward the children’s section, slowing down to a fast walk when a librarian gives him a slightly scolding look.

Light floods in from the gaps in the beautiful grating of the library’s fan-like southern wall, bending from the shape of the vaulted ceiling toward the thousands of books waiting on the shelves. Thanks to the shape of the ceiling, the light bends indirectly, such that customers’ shadows do not fall on the bookshelves. The vaulted concrete building makes Anneli catch her breath.

Originally, the vaulted ceiling was going to be plastered flat, but when the Academician saw the feats of the Ostrobothnian carpenters – the beautifully curving remains of the wooden formwork – he asserted: “No plastering!” Aalto felt that Ostrobothnians had always known how to build boats and ships. The skilfully executed wooden formwork of the ceiling was a prime example of this. Time rushes on. Anneli has decided to borrow a few classics from the library. Matti-Alvari doesn’t get a chance to glance at the books for loan in his amazement. Outside, Anneli tells her son how the blue tiles of the City Hall across from the library change colour from dark blue to golden brown in different light. Matti-Alvari tries squinting at the wall of the City Hall, but the tiles still look blue as ever to him.

Aalto Library

• Alvar Aalto designed 11 libraries in all, of which experts call the Seinäjoki City Library ‘the gem of Aalto libraries’.

• The fan shape of the circulation area is the building’s most original architectural feature.

• Aalto designed a grating for the large windows facing south to bend the intense rays of light. The grating became one of the more beautiful details of the library’s façade.

• Now the Aalto library is connected via an underground walkway to the newer Apila library designed by JKMM Architects.

• The library’s restoration was completed in 2012.

We can see the churc

Anneli squints and shades her eyes with her hand as she looks toward Lakeuden Risti’s high tower and the ridgeline of the church building. It is visible from here, she realises. She is standing in the exact same spot where years before she saw the height of the upcoming parish centre’s wall being measured by eye. Just like then, the weather is beautifully calm and sunny now in the summer of 1968.

When the parish centre was being built, people were afraid that the parish centre, which would surround the church in a U shape, would block the view of the church. Alvar Aalto had been thinking the same thing as he measured the view. For this reason, Aalto had had to remove the roof from the parish centre’s outer terrace, as well as shorten the north wing’s length and extend its width, to keep the building’s area the same.

The congregation had long deliberated how they would be able to afford the parish centre planned for the church grounds. They were desperate for a new space, however. The decision became easier when the loan market began to look better, and church tax became prepaid in 1960.

Seinäjoki’s new procurement still ruffled feathers all the way up to the diocese; in question, after all, was a large expansion of the church grounds in a community of 15,000. The parsonage originally in the plan

was left unbuilt, however, which in its own way actually helped the approval of the project – although this was done without asking Alvar Aalto’s opinion.

Anneli goes up the wide steps leading to the church yard from School Street. The sheltered church yard would be very suitable for holding even a large church event. She leans against the parish centre’s terrace railing and admires the view, which includes City Hall, the library and further to the west, the Central Government Offices, which are under construction and also designed by Alvar Aalto. This is really starting to look like a city centre, Anneli thinks.

Parish Centre

• On the western side of Lakeuden Risti, a U-shaped parish centre surrounding the church yard on three sides was built in 1965-66.

• Aalto designed the church yard in such a way that it would be possible to hold outdoor events there.

• The same timber was used in the parish meeting hall as in the interior of the church.

On a visit to the Central Government Office

Matti-Alvari is a second-year student in primary school and is going to his mother Anneli after the end of the school day. His mother works in the brand-new Central Government Offices. It is December 1968. The eight-year-old boy jumps over piles of snow in the yard. Suddenly he begins to peer at the façade of the government offices. He looks closely, covers one eye and looks again. Once inside, he climbs up to the second storey to his mother’s office and asks: ‘Mother, does this building have two or three storeys?’ His mother also thinks that the building looks like it has two storeys, when it actually has three.

At the time of the town hall contest, people began to envision that Alvar Aalto could also design the Central Government Offices in order to complete the set. Construction slow, since permission for approval of the property and approval of the building’s design had to be sought from the central government. Two years passed before the government approved the room plan. According to the plan, the government offices would in time house the Ilmajoki District Court, a police station, tax office, employment agency and the Seinäjoki military district..

In Aalto’s opinion, the government offices should hierarchically be more modest than the other buildings of Seinäjoki’s administrative centre. Thus the height of the building could not exceed two storeys. However, the building was built with three storeys. Aalto’s vision was to make the government offices a ‘calm background building’

as an endpoint to the administrative centre. But he did not a want an overly sober-looking building. Aalto thought that the building’s façade should be lively. He tried to implement this with the varied spacing of the window dividers and the slanted wall on the southern end.

‘Let’s go to the district court hall’, Anneli suggests to her son. ‘I need to take important papers there for the hearing.’ In the district court hall, the boy’s mother says that this room is the building’s most significant space architecturally. In Matti-Alvari’s opinion there’s nothing special about the room. However, the sharp-eyed Matti-Alvari notices that there are many details in the Central Government Offices similar to what he has seen at the City Hall. His attention is especially drawn to the wall surfaces made of wooden slats.

Central Government Offices

• n Seinäjoki, it was considered necessary to have the administrative centre as an architecturally unified whole, so the Central Government Offices would also be located in the same area and the designer would also be Alvar Aalto. The central government agreed to the procurement after many phases.

• The government offices became the endpoint of the axis departing from the church and crossing the Citizens’ Square.

• Nowadays the government offices building is owned by the city and used as workspaces for officials.

Alvar Aalto’s passing

Matti-Alvari is 16 years old, and sees that his mother is sad. Anneli reads in the day’s Ilkka newspaper that the architect Aalto, whom she so admired, has had a heart attack and died at the age of 78. Anneli and Matti-Alvari had just driven to Alajärvi the weekend before and visited the gravestones that Aalto had designed for his mother and father. At the same time they admired the nearby buildings designed by Aalto.

‘Not just Finland, but the whole world has lost one of its most notable architects’, Anneli reads aloud, and then continues: ‘Aalto was a powerful influencer. He was a mentor to an entire generation of architects both here and abroad.’

The boy’s mother knows that then again Alvar Aalto often had to ‘flounder in deep snow’ in his work. Aalto’s career was long and productive. He had even been recognised as an architectural genius, even though he not all parties or all ages approved of him. Especially in the last few years, opposition had been a bitter pill for Aalto. In particular, these included the design for Helsinki’s city centre which was never built.

Alvar Aalto was truly excited about the design for the whole of Seinäjoki’s buildings. We know that in the morning in his office, he always rushed first to the Seinäjoki design table. However, he was also disappointed in Seinäjoki by the fact that it was not possible to implement his design for a theatre on the schedule he wished.

Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto

Architect, designer, Academician

Born 3.2.1898 in Kuortane

Died 13.5.1976 in Helsinki

• Moved to Jyväskylä with his family when he was 5 years old and went to school there.

• Spent his summers both as a child and an adult in Alajärvi, where there are several buildings designed by him. Aalto is registered in Alajärvi during the years 1918-1925.

• He completed his schooling as an architect in 1921. First architect’s office in Jyväskylä in 1923. Married architect Aino Marsio in 1925.

• Architect’s office in Turku 1927. Significant buildings in the functional style in the 1930s, such as the Viipuri Library and Paimio Sanitorium.

• The couple’s furniture and glassware design began in the 1930s. Artek was established in 1935.

• Selected as chairman of the Finnish Association of Architects in 1943. Widowed in 1949.

• Married architect Elissa Mäntyniemi in 1952. Title of Academician 1955.

An all-encompassing theatrical experience

Anneli is very happy, when the Seinäjoki City Theatre is finally completed in 1987. She has purchased tickets to the opening show, Symposium, for herself and for Matti-Alvari, who is interested in the world of theatre. She is also excited that her son will get away from his university studies for the weekend and come home for the first time in a long time.

By now it has been almost 20 years since Alvar Aalto drafted the main drawings for the Seinäjoki theatre. The completion of the Seinäjoki administrative centre was delayed for many reasons, however. The greatest reason was that our country concentrated closely on building a welfare society during the turn of the 1960s-1970s. Things were built for children, youth, the sick and the elderly. This meant that construction of cultural institutions shifted to the back burner.

In Seinäjoki, the theatre was even envisaged in another location, but in the end it wound up in the location in Aalto’s site plan. Aalto’s wish that he might come to Seinäjoki once more in his lifetime to see the whole administrative centre completed did not happen. The theatre was completed posthumously under the direction of Elissa Aalto – 11 years after Alvar Aalto died. The theatre was constructed according to Aalto’s design as much as was possible in the changed circumstances.

Anneli and Matti-Alvari arrive in the theatre’s lower foyer. It is full of people, but the space still feels expansive. While waiting for the coat hooks, Matti-Alvari’s attention is caught by the floor tiles, where he seems to see images shaped like herring bones. ‘You saw correctly’, Anneli remarks. ‘I’ve heard that this flooring is made of limestone tiles from Öland and over time, fossil figures have become engraved in them.’

Before the start of the show, mother and son have time to enjoy pastries and coffee in the theatre’s restaurant. Anneli finds the theatre restaurant, which is furnished with Artek furniture and lamps, very beautiful. She feels like she could sit in the wicker chair forever.

Anneli and Matti-Alvari go up the theatre’s stairs. The upper foyer is full of people who have come for the opening. The atmosphere is somehow anticipatory and festive. Once they step into the main stage auditorium, Anneli whispers to her son: ‘Look, what an amazing curtain!’ Previously, Anneli has only seen red velvet curtains in theatre halls. This is something totally different. The curtain reminds Anneli of a giant, broad abstract painting,

where large squares shine in primary colours, with white, grey and black lending wings to overall effect. She has heard that the curtain was designed by a renowned Finnish artist, whose name she can’t remember just now. Anneli and Matti-Alvari take their places on the wide, black bench. The hall darkens and the show begins.

As they walk out of the theatre after the show, Anneli and Matti-Alvari wonder at the feeling that lingers after the visit to the theatre. The modern and reductionist setting of the new theatre, yet with its luxurious interiors, and the unusual show have created in their minds a whole which they would like to still remember around an evening cup of tea.

At home, Matti-Alvari tells his mother that for some time now, he has been dating a nice girl. He reveals that they are actually secretly engaged and says he will soon bring the girl to meet her. He also says that they intend to get married the following summer. He goes on to say that they’re thinking of holding he wedding in Seinäjoki.

The following day, an early autumn day, Anneli and Matti-Alvari have each decided on their own to pop by the Lakeuden Risti tower, where Matti-Alvari has not been before. Over time the Lakeuden Risti Church with its tower has become one of Alvar Aalto’s most internationally recognised works among the general public. The Seinäjoki Aalto Centre has begun to draw tourists interested in Alvar Aalto’s architecture, even from abroad.

It is possible to go up the Lakeuden Risti tower by climbing stairs, but Anneli and Matti-Alvari resort to the elevator. At the top, Matti-Alvari pushes the tower’s heavy iron door open. An early autumn gust of wind takes hold of their hair when they step out onto the tower’s concrete floor.

The Lakeuden Risti bell tower forms a cross, which functions as a viewing platform for the South-Ostrobothnian landscape on all sides. Anneli and Matti-Alvari realise that the views are better than they imagined. From here, one can make out the whole city, the central hospital, Jouppila Mountain, schools, and gaze further and further out to the horizon and toward the rest of the province. They especially admire how the administrative buildings of the Aalto Centre look from a bird’s eye view.

Suddenly Anneli has an idea: ‘What do you say, Matti-Alvari – could you two be married next summer here in the tower!?’ ‘Hmmmm’, mumbles Matti-Alvari. ‘Here, eh? Well, I’ll have to think about that. Here we’re pretty much at the mercy of the weather, since there’s no roof. But this would be quite a unique place for a wedding.’ Matti-Alvari promises to mention his mother’s idea to his girlfriend, however. Anneli, meanwhile, asks the congregation whether a wedding in the tower would be possible.

Seinäjoki City Theatre

• Built posthumously according to Aalto’s designs under the direction and supervision of architect Elissa Aalto from 1986-87.

• The curtain was designed by the artist Juhana Blomstedt.

• Originally the building was supposed to be a concert hall and congress centre in addition to a theatre.

• The theatre now has four stages: as the largest, the 429-seat Alvar Hall; the smaller Elissa Hall; the Workshop Theatre and Aino Stage, as well as a theatre restaurant, where performances can also be put on.

See you at the square!

It is a warm and sunny late summer Saturday in 1988. It is getting on toward afternoon. There is excitement in the air at the base of the Lakeuden Risti tower. Aalto-enthusiast tourists who look Italian are trying to get into the tower, but the sexton tells them in English that a private event is about to begin in the tower.

The sexton leads four people into the elevator and takes them up into the tower. After a little bit he comes to get the priest and the musician. The young couple is left waiting.

At last the sexton retrieves the excited and nervous Matti-Alvari with his bride. The iron gate of the elevator closes. After a moment the elevator begins to rise jerkily but steadily upward. The bridal couple squeeze each other’s hands. After a bit, when they go down the elevator, they will be a married couple

The elevator stops at a landing, after which one must ascend by foot up twenty or so steep stone steps. The bride holds out her bouquet of flowers to the groom, lifts the hem of her bridal gown and begins to climb up the steps, hoping that she won’t trip in her high heels. Once they have climbed up, the sexton, who went before them, opens the door to the cross-shaped tower’s landing for the bridal couple. The couple feel a breath of warm summer wind on their faces. Music can be heard nearby.

Meanwhile, more people in festive clothes gradually gather on the inner courtyard of the Aalto Centre, the Citizens’ Square. As the clock nears the appointed hour, everyone begins to look toward the Lakeuden Risti tower. It is hard to see, however, whether something is happening on the cross-shaped tower.

Children run around and play near the water fountains. The spray from the fountains feels refreshing on such a hot summer day. Some of the guests admire the surroundings of the square and the flowers on the ledge of the City Hall, thinking how nice it is that the Citizens’ Square was finished by this summer.

The natural stone of the square, which was influenced by Mediterranean piazzas, is broken up by straight-edged granite tile that reflects the sunlight and that leads the gaze to the various buildings of the centre. Construction of the Citizens’ Square in its current form became possible when the location of the City Library was moved nine metres south and its position relative to the City Hall was changed. Alvar Aalto had a vision of a square which would function as a gathering place for people as well as a place to hold congresses and meetings.

But here they finally come. The just-married couple comes down the stairs from the church yard, followed by the witnesses, pastor and sexton. Attentive drivers stop to let the party cross the road, and so they get to the other side, to the waiting festive audience.

Throwing of rice, congratulations, hugs, slaps on the back and tears of joy ensue. Many people have come to take part in the celebration, but there’s plenty of room on the Citizens’ Square.

After some time, Matti-Alvari and his bride get into the back seat of a very plainly decorated car. In the car, the couple’s journey would continue to his mother Anneli’s home, where the just-married couple would be celebrated with cake and coffee.

Citizens’ Square

• On the Citizens’ Square, light grey granite frames outline rectangles laid with small stones and thus form the finishing touch on Seinäjoki’s Aalto Centre.

• The Citizens’ Square formed in Aalto’s mind back during the architectural contest for the town hall. Later he highlighted the square’s nature as a gathering place for the people as well as a place for holding congresses and meetings.

• As construction of the administrative centre progressed, the Citizens’ Square stretched past School Street in the site plan. The idea of closing the street to vehicle traffic is as yet not implemented, however.

The world’s largest collection of Aalto glassware

Anneli hurries toward the Aalto Centre. She wants to be present when the collection of Aalto glassware of the retired former city architect Touko Saari is officially opened to the public. The city of Seinäjoki is now the owner of the collection after many controversial phases. Another donation drive from the general public was organised in order to obtain the collection. In the end, the city council voted on the fate of the collection. Votes for and against were evenly divided. The chair took the decision on the acquisition. The collection, which the city architect had collected for over 50 years, was now transferred to the city of Seinäjoki.

The year is 1998, and if Alvar Aalto were alive, he would now be 100 years old. Anneli muses that Matti-Alvari and his wife also have a special date coming up, their 10-year wedding anniversary. ‘I wonder how they’re going to celebrate?’ Anneli thinks. ‘Actually, I could buy something for them as a memento of the anniversary. I’ll have to think about what, though.’

Anneli meets a friend from work at the opening of the glassware collection. They chat about how great this decision is, that the collection will now stay together and stay in Seinäjoki. The world’s largest single collection of Aalto glassware is made up of over 200 glass items designed by Aino and Alvar Aalto. They primarily designed them in the 1930s. The collection includes the winning pieces of major glass design competitions, such as Aino Marsio-Aalto’s Bölgeblick series, which from then on was known as the Aino Aalto glass series.

The Riihimäki Flower exhibited at the Milan Trienniale and the Aalto Flower created for the New York World’s Fair were jointly designed by the architectural couple.

The opening is festive. The climax is when Saari gives the city of Seinäjoki a bronze statue made by the Academician and sculptor Wäinö Aaltonen. The bust given as a gift was made when Alvar Aalto was 50 years old. ‘Where will the city put this bust?’ Anneli wonders in her mind.

Anneli joins the crowds of people looking at the items. She admires how many amoeba-shaped wares there are in the collection, from shallow dishes to tall vases. She knows that at one time, these vases created by Alvar Aalto were made for the Karhula-Iittala glass competition, and they represented brave and experimental modern design. They were shown for the first time at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, in the Finnish pavilion designed by Aalto. Later the most popular model of these vases got the name Savoy. Almost 20 years later, the same vase began to be produced as a series and got the name ‘Aalto vase’ in the 1970s.

Gazing at the vases, Anneli has an idea: ‘I’ll go by the Lehtinen department store and buy an Aalto vase for the couple celebrating their ten-year anniversary. It suits them, since they value Finnish design and the imprint Alvar Aalto left on our country’s history.’

Aalto Glassware Collection

• The Aino and Alvar Aalto Glassware Collection includes over 200 glass items designed by them.

• The city of Seinäjoki acquired the collection in 1997 from the retired city architect Touko Saari.

• The star of the collection is the large glass vase designed by Alvar Aalto as a 50th birthday gift for Aino Aalto.

• The glassware collection is open to the public at the Aalto Library in Seinäjoki.

References

Aaltonen, Markus (2004). Näkyyhän se varmasti. Alvar Aalto ja Seinäjoki. (I’m sure we’ll see it. Alvar Aalto and Seinäjoki.) Seinäjoki: Veterator.

Aaltonen, Markus (2012). Vapaata viivaa. Kriipooksia Alvar Aallosta. (The Free Line. The marks of Alvar Aalto.) Seinäjoki: Veterator.

Hautanen, Raimo (2014). Maailman suurin Aalto-lasikokoelma. (The World’s Largest Collection of Aalto Glassware.) Nykypäivä 10.1.2014.

Kamila, Marjo (2013). Maailman suurin Aalto-lasikokoelma. (The World’s Largest Collection of Aalto Glassware.) Unprinted publication. City of Seinäjoki: Aalto Cultural Travel Project.

Lahti, Louna (1997). Alvar Aalto ex intimo – aikalaisten silmin. (Alvar Aalto Ex Intimo – in the eyes of his contemporaries.) Jyväskylä: Atena Kustannus Oy.

Pakoma, Katariina, ed. (2011). Alvar Aalto. Seinäjoen kaupunkikeskus 1951 – 1987 (Seinäjoki’s City Centre 1951 – 1987) Jyväskylä: Alvar Aalto Museum.

Schildt, Göran (2007). Alvar Aalto. Elämä. (Alvar Aalto. His life.) Jyväskylä: Alvar Aalto Museum.

Electronic resources

Ilkka (1976). Akateemikko Alvar Aalto on kuollut. (Academician Alvar Aalto has died.) Ilkka 13.5.1976. https://www.ilkka.fi/mielipide/yleis%C3%B6lt%C3%A4/akateemikko-alvar-aalto-on-kuoNut-1.2049559 [accessed 21.1.2018]